Major central banks typically cut interest rates in response to economic stresses; they ease when the data force them to do so. Some important exceptions in recent history happened 1) in 2016 when Mark Carney’s Bank of England cut rates as a cushion against the potential downsides of the pro-Brexit vote, and 2) when the Bank of Canada cut its rate in response to the steep drop in oil prices. During both policy changes, the central banks reassured markets that the rate cuts were just precautionary. Both cuts have since been rolled back. On CNBC on Friday, March 29, Larry Kudlow, President Trump’s National Economic Council Director, shared his and the President’s opinion that the Fed should cut rates by 50 basis points as a buffer against global economic weakness.

Kudlow insisted that the U.S. economy is perfectly fine and rattled off its strengths. He emphasized that there is no emergency. Either of these conditions by themselves represent an argument against any rate cut. Combined, these conditions make a rate cut a non-starter. So clearly Kudlow must be worried about something. He provided two clues: the inverted yield curve and Q4’s big drop in commodity prices.

Just last week I covered the potentially ominous economic signals coming from the inverted yield curve. In his CNBC interview, Kudlow effectively confirmed we should all be watching the inversion with some concern. Accordingly, I will be referring to this post as much as possible as the market works out its chosen interpretation of the inversion.

The reference to the drop in the commodity index confused me because the commodity indices have almost fully recovered from that decline. It does not make sense for the Fed to cut rates in response to something that is almost over.

Source: TradingView

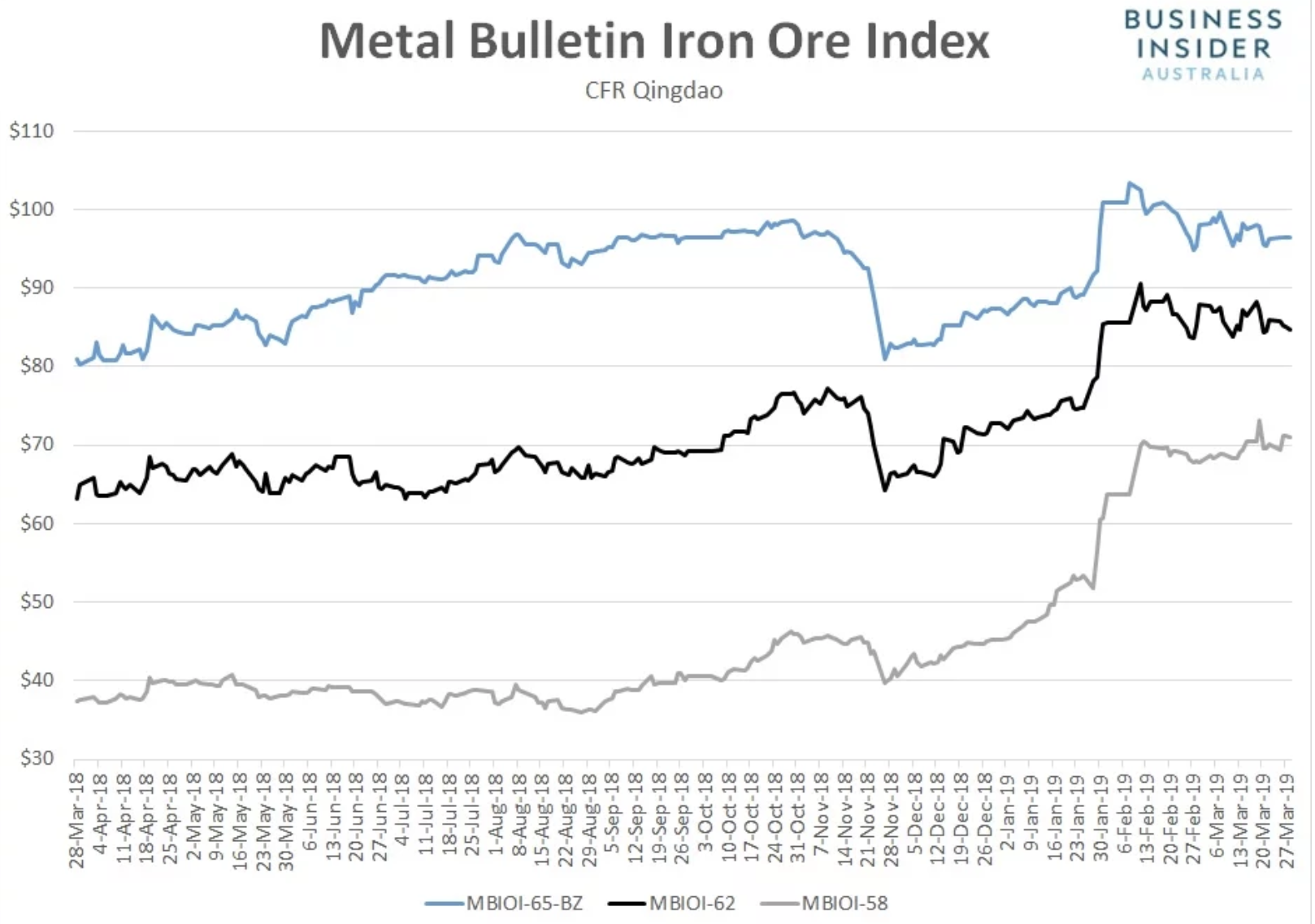

The Dow Jones Commodity Index (DJCI) consists of petroleum, copper, soybeans, cattle, and wheat. Iron ore, which in many ways is more economically important given China’s massive consumption of the commodity, followed a different pattern given supply issues. Iron ore suffered only the briefest of pullbacks in November and rallied from there.

Source: Business Insider Australia

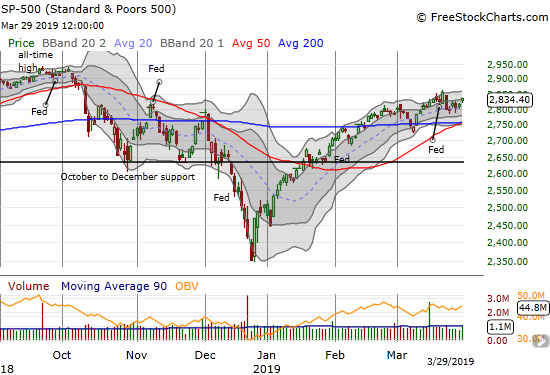

I think the more important point about Kudlow’s commodity reference is that he probably used it as a proxy for the stock market. The stock market plunge coincided with the decline in commodities.

Source: FreeStockCharts.com

In other words, the drop in stock prices freaked out Kudlow and company just as much as it freaked out the Fed which in turn capitulated on its planned rate hikes for 2019. I can only imagine the groans from Chair Jerome Powell as he internalizes the implications of Trump failing to find mollification in the Fed’s now deeply dovish stance. I call this phase the “disindependence” of the Fed.

Kudlow was very careful to reiterate that he believes in the independence of the Federal Reserve. Those assurances are moot when married to a strong opinion of what the Fed should do. The Fed officially stays independent, but in practice, the Fed is not independent as it responds to cues from the White House: disindependence.

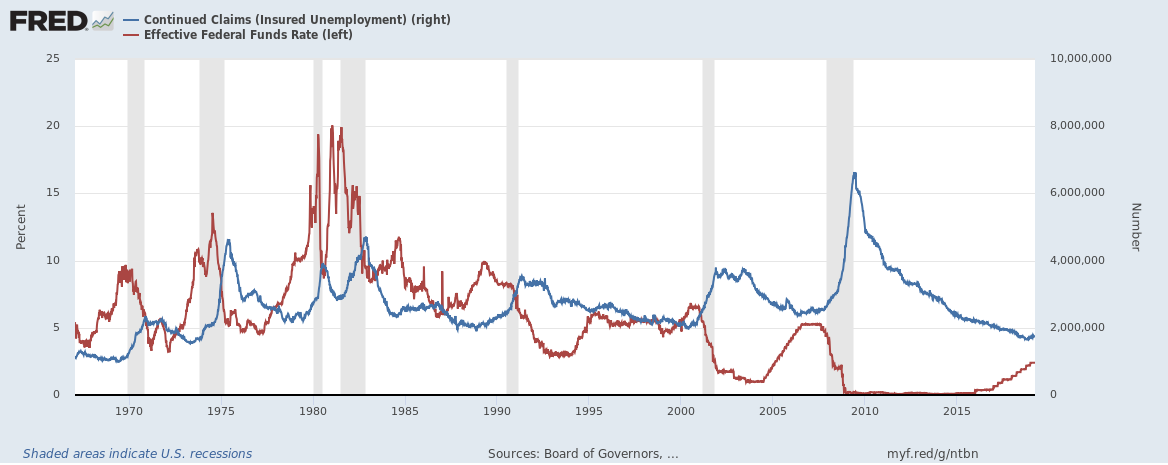

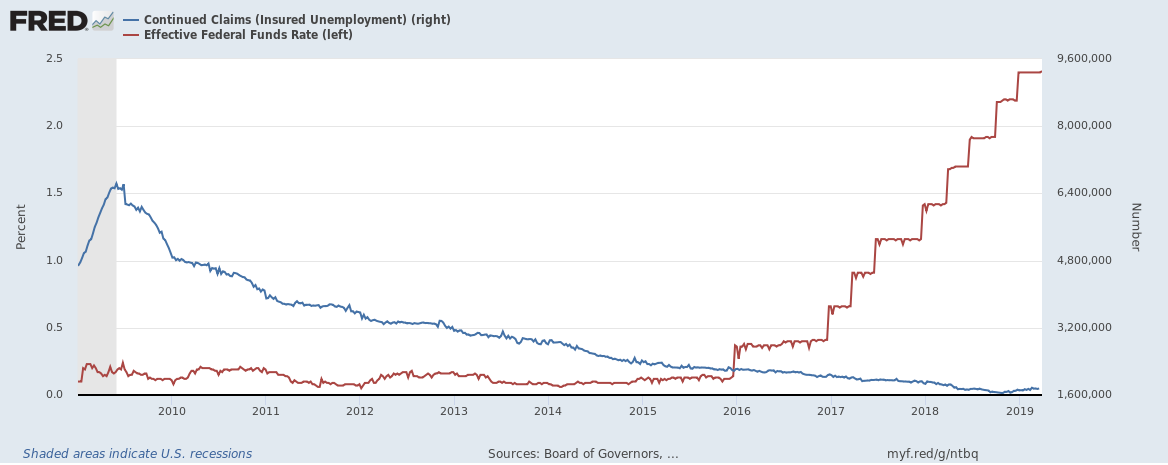

Interestingly enough, there is a case for worrying directly about what the Fed is doing. Last year, I reprised a post on “The Fed-Related Chart That Most Concerns the Stock Market which showed how the peak in a Fed rate-cut cycle often precedes a recession. The Fed keeps hiking until some data or process convinces it to stop. Unfortunately, the seeds of the next slowdown have apparently taken root by then. In today’s case, the process underway may be a bottoming in continued claims for unemployment. Continued claims have not risen this long since the recession ended.

Sources: U.S. Employment and Training Administration, Continued Claims (Insured Unemployment) [CCSA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Effective Federal Funds Rate [FF], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, March 31, 2019.

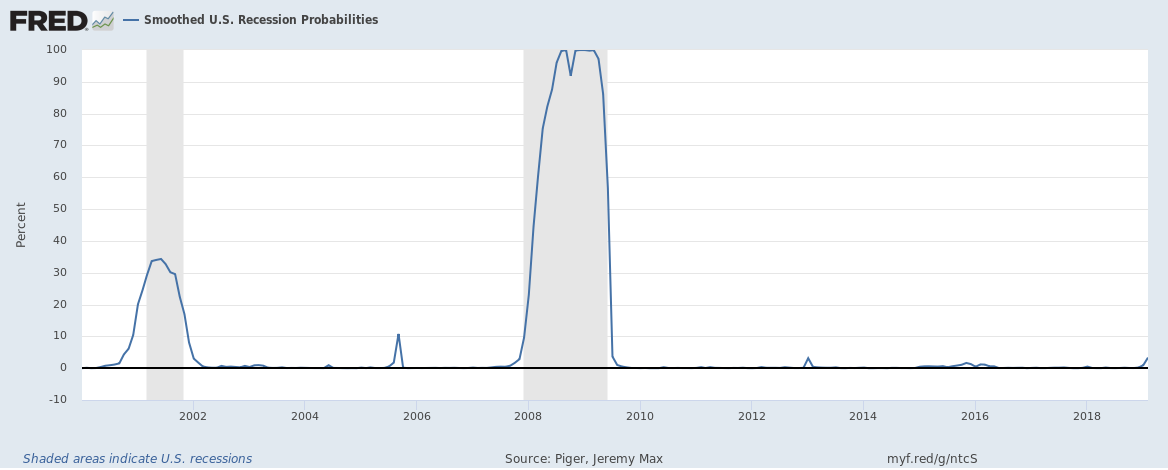

So if the Fed is truly done hiking rates, combine an inverting yield curve with a sprinkling of a White House spooked into asking the Fed for help and I see a risk of recession considerably higher than the 3.2% odds from February’s read from the St. Louis Federal Reserve.

Source: Piger, Jeremy Max and Chauvet, Marcelle, Smoothed U.S. Recession Probabilities [RECPROUSM156N], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, March 30, 2019.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: no positions

In my nearly 50 years of watching the Fed, every recession has been preceded by the Fed saying “risks are currently balanced, but we’re watching the data to see whether we need to adjust anything”.

This situation exemplifies why Kudlow should not be directing anything more important than a home movie. Kudlow says (paraphrased) “the Fed must ignore the administration”, and in the next breath, “the Fed should cut rates”. Obviously Kudlow wants to be seen as trying to prevent a recession. Since he can’t directly influence the Fed, he hopes to do so indirectly by influencing the CNBC (and wider) audience. Apparently his analysis is not sophisticated enough to realize that if he succeeds, the audience will begin to prepare for a recession, counter-productively catalyzing one. Will the Fed react in time? If they’re ruled by the incoming data, no.

Perhaps Kudlow thinks a recession is inevitable, and is merely trying to ensure the Fed gets blamed for it. But if that’s the case, why not instead advocate fiscal stimulus? That is something the administration can actually do, and which would at least postpone or ameliorate a recession, and maybe even prevent it. Perhaps he has an ideological or political problem with that approach?

A classic problem of policy makers: they have to dance lightly around predictions of economic calamity out of concern they could set in motion a self-fulfilling prophecy. I didn’t think about how his message could really be focused on the financial class. If enough investors start clamoring then those odds of a rate cut by December will jump from the current 50% to something a lot higher. This forcing the Fed’s hand. I need to start tracking those odds regularly again.