“One-Twenty Two” is a different narrative for students and fans of financial markets. This blog often examines the investing and trading implications of extremes in financial markets. By definition, an extreme condition marks a top or a bottom in prices and invites contrary thinking. For example, the cyclical concepts of “overbought” and “oversold” measure temporary extremes in the stock market. The economy has analogues in the booms that generate economic exuberance and the busts that cause depths of despair.

Displays of Economic Exuberance

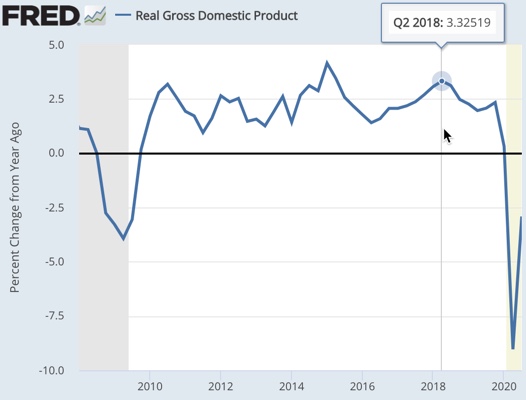

When economics mixes with government, promises of boom run far and long; busts can be prevented. A great example, an extreme one even, happened two years ago. Larry Kudlow, the leader of President Trump’s National Economic Council, set in motion an extreme in economic exuberance. In the wake of a two year uptrend in GDP growth from its trough in the second quarter of 2016, Kudlow declared “We are in a hot economic boom. There’s no end in sight.” At the time, I compared the pronouncement to the complacency that accompanied the “Great Moderation” of the latter Greenspan years (Alan Greenspan was the chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006). I claimed that “Kudlow issued a sound bite that *I* am confident will one day in the not-so-distant future sound cringeworthy to those of us who follow economics.”

That future is already here. Before the pandemic took the economy down, GDP growth was already decelerating. Indeed, Kudlow’s triumph celebrated the exact peak of economic growth over the last 5 pre-pandemic years. Kudlow thumped his chest from the proverbial top of the hill with nowhere to go but down.

The Federal Reserve to the Rescue

Fortunately for Kudlow and the rest of us, the Federal Reserve was determined to delay a potential recession as long as possible.

Decelerating GDP growth convinced the Federal Reserve to reverse course on monetary policy in 2019. At its July 31st, 2019 policy announcement, the Federal Reserve announced a 25 basis point cut in its policy rate to the 2-2.25% range. This cut was an abrupt change from the almost steady adjustment higher in interest rates that began in December, 2015 (a steady ascent started a year later). Chair Jerome Powell famously called this move a “mid-cycle adjustment.” In the statement, the Fed observed that “this action supports the Committee’s view that sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective are the most likely outcomes, but uncertainties about this outlook remain.” In other words, the economy remained too fragile to sustain even a modest attempt to normalize rates.

The stock market initially smelled trouble in the wake of the Fed’s course correction. The S&P 500 (SPY) fell 1.1% that day of the mid-cycle adjustment. The index continued to sell-off for three more trading days. The S&P 500 failed to print a net gain from the July 31st monetary policy decision until October 25th. By that time, the Fed had cut rates three more times. Those cuts provided enough fuel to launch the market to its last pre-pandemic all-time highs. In almost four more months, and one more Fed rate cut, the index gained 12.0%.

The Good News in Declining Unemployment Rates

The good news underneath the decelerating economy and a vacillating stock market was a continued decline in the unemployment rate. Kudlow often celebrated these numbers with his classic exuberance. From its peak in October, 2009, unemployment steadily and consistently declined until the pandemic brought the reliable downtrend to a screeching halt.

This declining unemployment rate helped to maintain faith in a strong economy. The labor situation had to accompany any description of the economy’s strength. Indeed, the healthy labor market made some wonder why the Fed needed to cut interest rates at all. (I created an “economic reality” index to track the relationships between the Fed balance sheet and various measures of the health of the labor market.)

The Trade

We will never know how much more time remained before the economy finally descended into its next recession. The coronavirus pandemic completely upended the existing narratives and forced everyone to invent new playbooks. Instead of gliding into an economic slowdown, the economy crash landed into a deep recession.

Kudlow’s economic exuberance was not the first example of policy over-confidence, and it will surely not be the last. Extremes are not sustainable no matter the government, no matter the political party. Students and fans of financial markets should always consider the merits of leaning against the extremes whether that means investing, trading, and/or managing personal finances. Do not celebrate, do not despair: robustness and sobriety over hubris and complacency.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: no positions

Bravo!