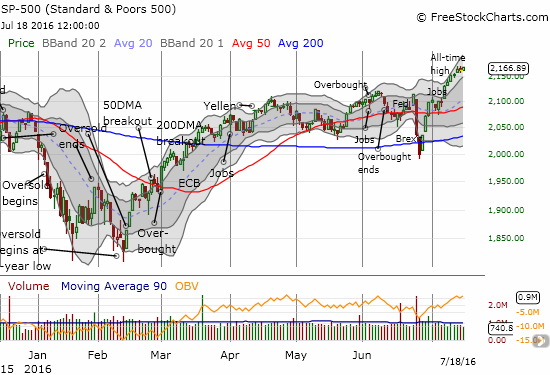

“Faint and quaint” is how I am starting to describe the initial panic and consternation of financial markets resulting from the UK’s decision to exit from the European Union (EU), aka Brexit. The S&P 500 (SPY) now logs new all-time highs as if nothing ever happened. Yet, a rapid consensus has grown around reducing forecasts for global growth as a result of Brexit. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) joined the chorus on July 19, 2016:

“As of June 22nd, we were…prepared to upgrade our 2016-2017 growth projections slightly. But Brexit has thrown a spanner in the works. The new WEO update gives our revised numbers compared to April when we were predicting 3.2 percent global growth of output in 2016, and 3.5 percent in 2017.

Today’s WEO update downgrades both of those numbers by .1 percentage point to 3.1 and 3.4 percent, respectively.”

This adjustment is minor of course. I still find it notable in that the IMF believes there will be any impact and that impact convinced them to reverse course on an economic upgrade.

The potential for global impact also appears in the statements of central banks. Last week, July 13th, the Bank of Canada slightly reduced its forecast of global growth while citing Brexit as a causal factor:

“…the results of the referendum in the United Kingdom have clouded the global outlook.

Governing Council carefully considered how best to incorporate the effects of the Brexit vote into the outlook. It is early days, and there will be a prolonged period of uncertainty as authorities work out how the United Kingdom will exit from the European Union. Governing Council decided to incorporate in the base case projection a 0.2 per cent reduction in the level of global GDP by the end of 2018. This reflects direct trade effects and some confidence effects on business investment. We are assuming that the Brexit process will proceed in an orderly fashion. Financial markets were resilient despite sharp adjustments in a wide range of global asset prices in the wake of the vote, and financial conditions are generally more accommodative.”

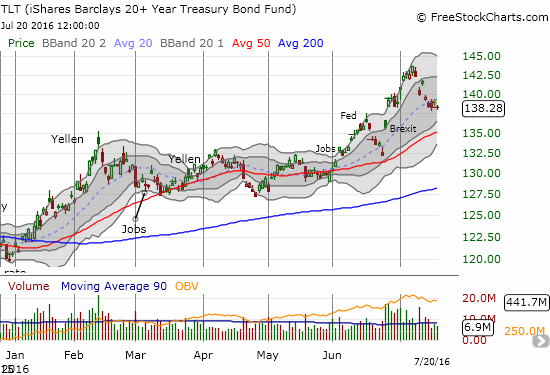

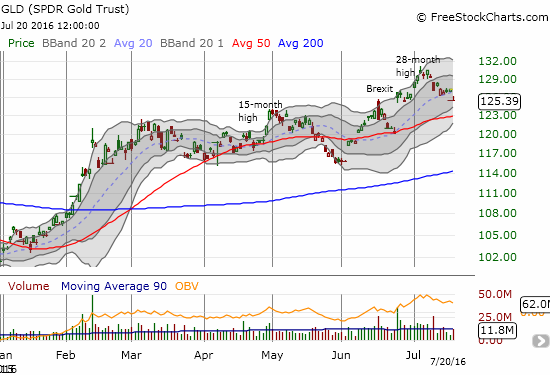

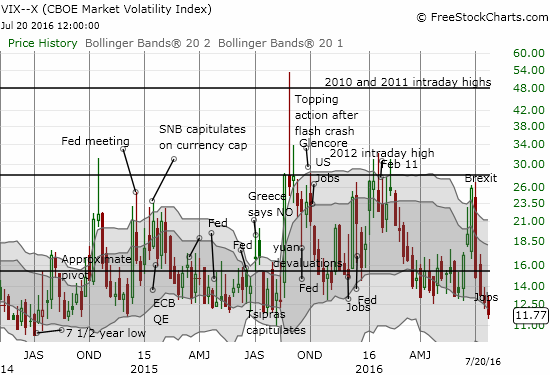

Two days before this statement, the S&P 500 (SPY) hit a new all-time high for the first time in about 14 months. At the same time, financial markets seemed to stick by bets on trouble ahead. Bond yields were at or near record lows, it took a political victory by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to arrest finally the strong rally in the Japanese yen (FXY), and gold (GLD) was trading just off 28-month highs. This apparent conundrum motivated someone during the Bank of Canada’s press conference to ask Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Wilkins and Governor Stephen S. Poloz for ideas on how to reconcile the mix of post-Brexit reactions in financial markets. The question focused in on stock markets versus gold and bonds. The question and then answer ran from the 17:35 mark to 22:00.

Presumably, low bond yields signal economic distress and elevated gold prices represent equal levels of market anxiety. Poloz’s attempt to reconcile and rationalize the mix of market reactions was instructive. I heard in Poloz’s sometimes rambling answer that there are parallel dynamics at work which can operate independently. Without saying it explicitly, Poloz described a situation where central banks have effectively driven a wedge between financial markets and economic uncertainty. The two are generally decoupled until a shock comes along to recouple the two. Poloz focused a lot on the impact of uncertainty and a lot less on the impact of central banks in distorting market reactions (no surprise there?). In other words, if you want to reconcile the various post-Brexit responses, don’t. Central banks have made it more and more difficult to do so! As you will see in Poloz’s response, he could only answer the conundrum with more conundrums…

Poloz began by conditioning his answer with the observation that the understanding of the Brexit shock is still in its early days. In other words, what we understand today as the post-Brexit fallout may yet change in a few more months. Poloz also noted that some stocks, particularly bank stocks across multiple markets, have not recovered their post-Brexit losses. However, he failed to explain then how stock markets could rocket back with financial firms still suffering. I tend to think of the health of financial institutions as being well-correlated with the health of financial markets. Rather than explain the apparent second conflict, Poloz simply concluded that the “risk-off” reaction was temporary.

Poloz then turned to the bond market as a completely separate issue. He offered multiple explanations for low bond yields. Poloz first pointed to the “unconventional monetary policy” of the European Central Bank (ECB) which has driven bond yields to extraordinary lows. Global bond yields tend to be highly correlated and have thus followed Europe lower. I was puzzled by his failure to point the finger at easing and easy central banks worldwide. The blame is not Europe’s alone.

Poloz next pointed to a “flight to safety” in the wake of Brexit in “certain markets.” He noted that there are “unmeasurable and unquantifiable risks” that drive a lot of uncertainty for businesspeople and their decisions to invest. This uncertainty has been an on-going theme since the financial crisis:

“We’re learning that the trauma of that experience, has left people uncertain and unwilling to take on risk given the same information set as before. They are more tentative and more risk averse. So it is taking longer for investment to recover generally around the world. If that uncertainty layer has now been given another reason to extend further. And if I characterize it that way, that risk is larger than it was before, and it just means we have to wait longer for clarity for that to recover.”

Once again, Poloz answered a conundrum with another conundrum. If so much uncertainty has lingered all these years, how have stock markets performed as well as they have at all? How have recoveries and rebounds delivered even more more assurance from nearly each and every sell-off? Stock markets suggest that these presumed uncertainties are not as salient or as strong as central banks think. Or perhaps the extraordinary accommodations from central banks has done little to cure uncertainty and unease in the real economy, but monetary policies have done plenty to bolster the confidence of the buyer’s of financial assets. Money more easily flows into inflating financial assets than into risky business propositions. I prefer this second explanation.

As if a multi-layered conundrum was not enough, Poloz piled on when he moved on to note how the U.S. Presidential election cycle is likely adding yet more uncertainty to the decision-making of businesspeople. He made this claim without a hint of irony given the S&P 500 was sitting around all-time highs. I would love to see evidence of the paralyzing impact of presidential election cycles because it seems to me that the economy would have a lot of trouble sustaining prosperity if it paid so much attention to politics with every election, domestic or international.

So while Poloz rambled a bit, the main point comes out crystal clear: the stock market and the markets which conventionally communicate and measure economic risk and anxiety of risk are uniquely decoupled thanks to central bank intervention. Accommodation has flowed much more into financial assets than into business investment. With every new shock, central banks get yet more tentative, more apprehensive, and more accommodative. Given the number of things to worry about every year, this dynamic is becoming a cycle with no obvious end. The more central banks try to manage downside risk, the more they seem to fail to resolve real-world economic uncertainties. The endpoint looks forever elusive. In the meantime, stock markets seem to perpetually benefit from frightened central banks and the resulting monetary policies of risk management. While uncertainty and higher stock prices do not reconcile, they sure seem to mix well these days!

Note that in the week after the Bank of Canada’s decision on monetary policy, measures of risk have finally started to give way to the strength of the S&P 500 (SPY)…

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: long GLD, long SSO call options, long TLT call spread