What a difference 19 months make.

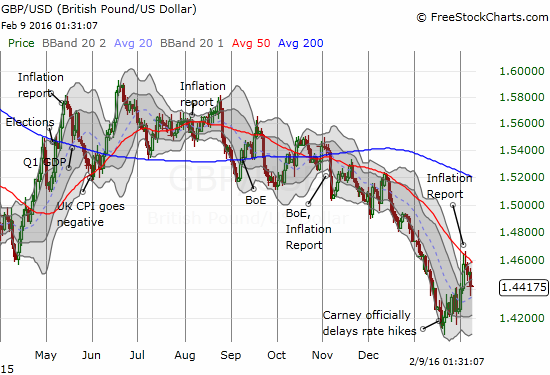

It was June, 2014 when Bank of England (BoE) Governor Mark Carney confidently warned financial markets that rate hikes could come earlier than implied at that time by the market. Less than a month later, the British pound (FXB) (or sterling) peaked against the U.S. dollar (DXY0). Peaks against the euro (FXE) and the Japanese yen (FXY) did not come until 2015. However, reality was soon clear: the Bank of England was in full retreat from its threats of rate hikes. This realization crystallized and received confirmation when a steep slide against all major currencies began in early December, 2015. The pound’s slide against the euro was particularly notable and has no doubt given the European Central Union (ECB) cause for pause.

One of the confirmations of the Bank of England’s intention to retreat from rate hikes came from Minouche Shafik, Deputy Governor, Markets & Banking. In a speech tellingly titled “Treading carefully,” Shafik explained why she hesitates to raise rates anytime soon (emphasis mine):

“…there is residual uncertainty about the relationship between the real economy and inflation – something economists refer to as ‘model uncertainty’ – which in this instance augurs for caution in setting monetary policy.4 The most likely outcome is that wage growth will soon resume its recovery, but there are alternative states of the world in which it takes longer for that to happen. So I judge it prudent to tread carefully, and refrain from voting for an increase in Bank Rate until I am convinced that wage growth will be sustained at a level consistent with inflation returning to target.“

Shafik noted that wage growth had recently plateaued, but acknowledged that the UK economy is generally well past the point where in previous cycles tightening would have begun:

Source: “Treading Carefully”, Bank of England.

On top of emphasizing a reluctance to raise rates, Shafik provided some revealing theory on the impact of the exchange rate on inflation. Given that the previous strength of the British pound will apparently suppress inflation in the United Kingdom for “several years to come,” I am assuming the BoE has an ingrained bias to avoid making moves to rekindle strength in the currency. All else being equal, the British pound could stay biased for weakness for much of the time it takes to wear off the disinflationary pressure from previous strength. From Shafik:

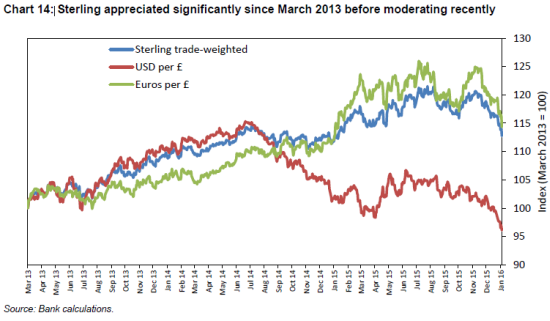

“Since 2008 we have learned more about how movements in the exchange rate, in particular, affect inflation. Contrary to the body of literature developed during the period of Great Stability, changes in the exchange rate do have a large and persistent effect on inflation through their effect on import prices. That means that the 18% appreciation of sterling which began in early 2013 (as the prospects for the UK economy improved relative to those of our trading partners) is currently exerting significant downward pressure on inflation and is likely to continue to exert some downward pressure for several years to come as lower import costs pass through the supply chain.”

Interestingly, Shafik still felt the need to remind the audience that rate hikes could come relatively quickly once the Bank of England finally got started. The quote contained echoes of Carney’s 2014 declaration (emphasis mine)…

“But once I am convinced, absent further shocks, I can see Bank Rate rising more quickly than the path implied by the market curve at the time of the last Inflation Report…

Personally speaking, should the downside risks from the world economy fail to materialise, and absent further shocks, once wage growth has returned to a level consistent with inflation returning to target I would expect the economy to warrant a path for Bank Rate that increases more quickly than implied by the market yield curve used to condition the November Inflation Report.”

Overall, Shafik clearly communicated a bias to avoid rate hikes in the short-term while attempting to maintain inflation-fighting credentials for the long-term. I am unclear on how to untangle the expectations of disinflationary pressures from the previously strong currency that will linger along with expected inflationary pressures from future economic performance.

A subsequent hint of a no-hike bias from the Bank of England came from a January 18,2016 speech at the London School of Economics by Gertjan Vlieghe, External MPC member. Vlieghe created the title “Debt, Demographics and the Distribution of Income: New challenges for monetary policy.” This speech was fascinating from beginning to end and for much more than just the interest rate implications. Vlieghe observed that today’s monetary policy goes beyond cyclical adjustments and now has been compelled to address structural issues and the fallout from global, macroeconomic pressures.

For addressing structural issues, Vlieghe wants central bankers to pay more attention to the “3 Ds”: debt, demographics, and distribution of income. Vlieghe points out that economists struggle to understand the persistence of low rates specifically because they are still using models that assume “…debt does not matter, there are no demographics and there is no distribution of income.” An examination of these 3 Ds suggests that the UK economy (and likely all other developed economies) will not revert to pre-crisis levels. This assumption rides within existing monetary models. Mean reversion is NOT in our future anytime soon.

Vlieghe uses this sober assessment of future economic performance to recommend caution and patience before proceeding with rate hikes:

“…for a given level of growth, real interest rates may remain significantly lower than in the past. The possibility of this scenario makes me more patient, other things equal, before raising rates, because we may not have to raise rates very much once we start. Moreover, the fact that, at very low interest rates, policy cannot respond as effectively to bad news as it can to good news also makes me more patient before raising rates…”

Vlieghe’s condition for hiking rates rests on a return of stable economic performance and upward trending inflation…

“…in order to be confident enough of the medium-term inflation outlook to justify raising Bank Rate, I would like to see more evidence that growth is stabilising after its recent slowdown, and that a broad range of indicators related to inflation are generally on an upward trajectory from their current low levels.”

With these conditions established, Vlieghe moves on to describe how the structural forces from the 3 Ds impact monetary policy.

Debt matters because the deleveraging process can limit the ability of the central bank to encourage more spending in the economy. Less spending in turn tends to depress inflationary pressures. A debt overhang thus generates “persistently weak recoveries” as consumers focus on bringing debt levels down instead of fueling economic activity through spending. With a lower bound on rates, the central bank can do little but wait out the deleveraging and avoid extending the process by hiking rates too early.

Demographics matter because longevity motivates more saving to the extent that retirement ages remain the same and declining fertility produces fewer workers who then require less investment. Higher savings and lower investment reinforce lower interest rates. However, since retired consumers save less and spend more, relatively speaking, they act against lower interest rates. The net balance of these forces is not formulaic, so it is a wildcard for the central bank to monitor over time. Demographics also evolve over long periods of time and could of course cross multiple business cycles.

Distribution of income matters because monetary policy can shift resources toward wealthier consumers who are more likely to save than spend. I believe Vlieghe is talking about the impact at the margins. More well-off consumers have fewer urgent spending needs than poorer households; this is especially true in the wake of a severe economic downturn. To the extent monetary policy does not help lower-income consumers, savings rates could increase further: these workers are forced to reduce spending in order to preserve future spending power. Vlieghe does not provide a novel prescription for dealing with an unbalanced income distribution. He merely suggests that rates must stay lower for longer to support lower income workers. The irony occurs when these same lower rates bolster the value of assets held by the wealthy which in turn can drive substantial income gains which finally further widen income distributions.

Vlieghe summarizes by integrating these forces in a way that points to slower economic growth:

“A high debt economy faces headwinds and needs lower interest rates. A high debt economy with adverse demographic trends needs even lower interest rates. And a high debt economy with adverse demographic trends and higher inequality … well, you get the picture.”

These reinforcing dynamics demonstrate why mean reversion is not likely coming out of the last financial crisis. Moreover, real interest rates “…will remain well below their historical average for a very long time, even with economic growth that is close to or only somewhat below its historical average…I think it is plausible that the appropriate real interest rate for the economy might be very low for years to come.” These policy implications have convinced Vlieghe that the Bank of England can stay patient ahead of raising rates.

Vlieghe’s conditions for hiking rates are very consist with Shafik’s conditions:

“With growth still slowing, and inflation pressures either easing outright or disappointing relative to forecasts, I do not believe the conditions are in place to warrant a rise in Bank Rate. I need to see further evidence that growth is indeed stabilising, and that a broad range of indicators relating to inflation, inflation expectations and pay growth are generally on an upward trajectory from their current low levels before being confident enough in the outlook to justify a rise in Bank Rate. In order to be confident enough of the medium-term inflation outlook to raise Bank Rate, I would like to see evidence that growth is not slowing further, and that a broad range of indicators related to inflation are generally on an upward trajectory from their current low levels.”

With commentary from the Bank of England like that from Shafik and Vlieghe, Mark Carney’s speech to set the direction for the Bank of England for 2016 was practically anti-climactic. On January 19, 2016 Carney delivered a speech called “The turn of the year” given at Peston Lecture, Queen Mary University of London. In this speech, he gave the official acknowledgement that the Bank of England put rate hikes on the shelf for 2016:

“Last summer I said that the decision as to when to start raising Bank Rate would likely come into sharper relief around the turn of this year.

Well the year has turned, and, in my view, the decision proved straightforward: now is not yet the time to raise interest rates. This wasn’t a surprise to market participants or the wider public. They observed the renewed collapse in oil prices, the volatility in China, and the moderation in growth and wages here at home since the summer and rightly concluded that not enough cumulative progress had been made to warrant tightening monetary policy.”

Note that Carney fully recognized that the market had already concluded that the Bank of England had to retreat from rate hikes. In classic form, the currency market also responded with a lack of surprise: the British pound finally stopped going down. For example, against the U.S. dollar, the pound (GBP/USD) began an upward climb. Essentially, for the short-term at least, everyone who wanted to play the rate hike news against the British pound was already in the trade. The official news is a time to close out positions, take profits, and relish being correct. This bottom is still holding against the U.S. dollar although its has given way to other major currencies like the euro and the Japanese yen (FXY).

Source: FreeStockCharts.com

The Bank of England continues to fascinate me with all its talk about taking action to drive inflation in one direction or the other. In reality, the BoE has done little but talk (outside of macroprudential policies) about inflation moving one way or another. The Bank has been in the business of trying to verbally guide market and consumer expectations about an inflation process that unfolds based on present economic conditions. This speech was no different:

“At present, the MPC is seeking to return inflation to the target in around two years and to keep it there in the absence of further shocks. We don’t want an overshoot of inflation.”

Carney reiterated the considerations in play for future monetary policy that would drive rate hikes. The Monetary Policy Committee wants to see actual and prospective progress on all three points before “…the initiation of limited and gradual rate increases”:

- The prospects for growth momentum in excess of trend consistent with eliminating spare capacity in the economy.

- Evidence of and expectations for a sustainable firming in domestic cost pressures.

- Developments in core inflation consistent with a reasonable expectation that total CPI inflation will return to the target in around two years’ time.

Source: Bank of England

Global disinflationary pressures are weighing on the UK. China is of course right in the center of this storm. Carney noted that UK exports to China have dropped by 1/3 year-over-year from November, 2014. Carney expects these pressures to continue and to weigh on domestic demand via the wealth effect and the financial tightening that comes from panicked markets. Like Shafik, Carney referenced past appreciation of the currency as a weight on inflation. Carney reminded the audience that “…around two-thirds of the effects of a currency move are estimated to appear in CPI inflation at horizons beyond one year.” According to the chart provided below, the trade-weighted British pound peaked just last November. Presumably then, currency-related disinflation will last at least through most of 2016.

Source: Bank of England

The members of the Bank of England were so effective in talking down the prospects of rate hikes that the most interesting moment of the latest Inflation Report (February 4, 2016) came when Carney had to address market odds of 30% that the Bank’s next move would be a rate CUT. From Ed Conway of Sky News:

“Governor, the markets are now pricing in the possibility – about a 30% possibility – of there being a rate cut rather than a hike in the next year. You’ve said repeatedly that you feel that the next move is likely to be up rather than down. Do you still stand by that?”

Here is the most important snippet of Carney’s response (emphasis mine):

“Absolutely. The whole MPC stands by that. We’ve just released our forecast which, as I mentioned in my opening remarks, is conditioned on a market path of interest rates…that 15-day average of the path of rates is rates sustained at current levels for a little while longer, and then gradually increasing father out over the horizon…

And in using that market forecast, based on our central view of the economy, we actually don’t achieve our objective. Let me put it a different way. Inflation gets back to target, but then it rises above it. So there’s not quite enough tightening in that market path that we used in order to do what the MPC is very clear – has been very clear about – is its objective, which is to return inflation to target in around two years and to keep it there – not to have an overshoot…

So as I said, again, and we said in the Minutes and in the Monetary Policy Summary, and was clear in the letter to the Chancellor, the view is that more likely than not, the next move in rates is up, and that is consistent with the forecast, yes.“

In other words, Carney is claiming that if rates stay at current levels for the next two years or so, inflation in the UK will get too high. So, at some point over this time period, the Bank of England needs to hike rates. This prospect is far enough into the future that the currency market is certainly not worrying about it. Instead, the more immediate concern for currency markets rests with the looming fear that the Bank of England could eventually join the growing number of its peers on retreat on rates.

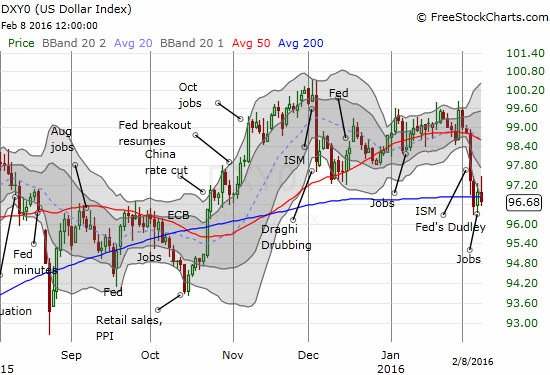

Oh how far expectations have dropped in 19 months! I cannot help but wonder whether the Bank of England has developed a blueprint for the U.S. Federal Reserve. Financial markets have priced away any rate hikes in the U.S. for 2016…

Source: FreeStockCharts.com

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: long and short various currencies against the British pound

Fascinating. Thanks for a great write-up!

Thanks! And thanks for reading!