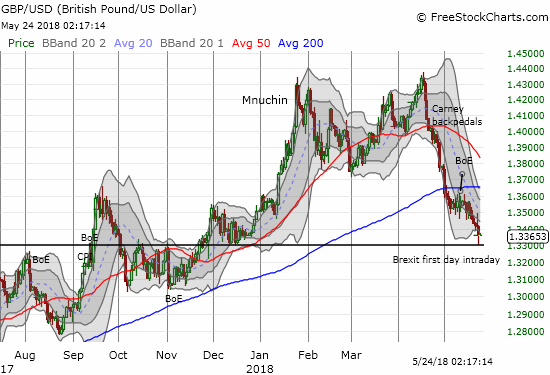

When U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin helped send the dollar careening with commentary welcoming a weak dollar, the British pound (FXB) surged enough against the then hapless U.S. dollar to make me speculate on GBP/USD reaching a blow-off top. GBP/USD did indeed pull back from that point, albeit in very choppy fashion, for almost a month and a half. A fresh rally from March to mid-April took GBP/USD marginally higher than the January peak before weaker economic data, fresh dovishness from the Bank of England, and a generally stronger U.S. dollar index plunged GBP/USD on a near relentless sell-off. Now GBP/USD just bounced off the intraday low reached on the first day of Brexit.

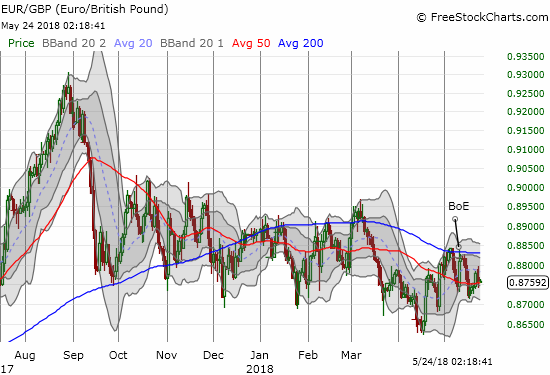

During the current sell-off, I went long GBP/USD as a small hedge against my net long U.S. dollar positioning. The long U.S. dollar positions performed so well that I finally took the loss on GBP/USD ahead of the Bank of England’s May Inflation Report on May 10th. With a clean slate on the British pound, I have focused mainly on fading the currency. The Bank of England provided absolutely no reason to bet long on the pound in its report or press conference. Trader disappointment is easier to see in the surge of EUR/GBP on that day.

Source for charts: FreeStockCharts.com

The press conference did not deliver any surprises for me, but I duly noted the palpable frustration expressed by some of the press about the vacillation of the Bank of England, and really Governor Mark Carney, on its readiness to finally get on with a rate hiking cycle. For example, here is a representative question (from the transcript):

“Kamal Ahmed, BBC. Governor, how worried are you that the tag of ‘unreliable boyfriend’ sticks, that households and businesses listening to you in February took the clear signal that interest rates were going to rise more quickly and to a greater extent than previously thought, they will listen to you today and say, ‘Oh, no, interest rate rises are now off for a longer period this year’? Can the audiences and the households and the businesses that you’re so keen to speak to trust what you say about whether interest rates are going to go up and, more importantly, when that is going to happen?…

Helia Ebrahimi, Channel 4 News. You’re trying to give clear guidance, but it ends up being confusing. All jokes about being an unreliable boyfriend aside, why is the Bank of England struggling so much to help consumers understand what’s coming, or do you think you’re doing a good job at communication”

Carney got a bit snippy with the first question and started his response with a sharp retort:

“Well, first off, Kamal, the households and businesses we speak to don’t trade short sterling, okay? They’re not fixated on whether we raise interest rates on May 10th or, you know, at the end of June or in August. First and foremost, what they want to know is the general orientation of the economy, that’s really what they want to know when we go around the country and speak to them…”

The response was odd since Kamal did not seem to indicate an interest in trading signals. Carney went on to paint a picture of a very sophisticated set of households and businesses. According to Carney they only care about the overall trend for rates and are quite content accepting that this trend could change at any given time…

“Now, knowing the general orientation of policy, that those interest rates are likely to go up, they do know that. They do have that sense, you know, slews of surveys and series of meetings tell us that, but they also expect that if the situation changes, they expect us not to be on some pre-set course, they expect us to be prudent, not passive, so if the situation’s appropriate, we will adjust policy.”

Just to make sure that the audience could feel the sting of some contempt, Carney even issued this zinger:

“So, you have to set policy to the circumstance here, provide the guidance, and I know it’s not what you necessarily want to hear, but in terms of it getting through to those who make economic decisions in the country, it does.”

In other words, the press’s interpretations and angst matter little. After all, the press does not get to make economic decisions in the UK anyway.

Undeterred, yet another question pointed out how the BoE confuses people with its wavering on the pace of rate hikes…

“Chris Giles, Financial Times. One of the reasons people might be a little bit confused about the bank’s stance is that you’ve said today that Q1 was erratic, an outlier, this wasn’t an important slowdown, it was temporary. You’ve also said that the economic momentum is the same as you thought it was in February, and yet the path of interest rates you’re, sort of, guiding on is significantly lower. In February, you said that everything’s the same. In February, you were being pretty hawkish and saying that financial markets weren’t expecting sufficient interest rate rises, and now you’re basically saying it’s okay. This is why people are confused. Could you clarify that?”

Carney’s response meandered through what amounted to mathematical excuses. The end of his response summed up the truly important message:

“…given what’s happened on the external side, that combined with the weak first quarter means it makes sense to step back, say, ‘Okay, we think momentum’s going to be re-established, but let’s see evidence of that before moving.’”

It is a response that reveals the BoE’s true, underlying tentativeness. Like a wary squirrel, the minute the BoE senses just a hint of economic danger – even when that danger is soft-pedaled as the temporary result of poor weather, “idiosyncratic factors” – the BoE immediately and eager rolls back any hint of previous hawkishness.

Carney so effectively circumvented the real issue of the Bank’s persistent vacillation on its policy stance that the next reporter had to press on:

“Larry Elliott, Guardian. Can I just follow up on that? In February, you did say that you thought monetary policy would need to be tightened somewhat earlier and by a somewhat greater extent. You’ve now dropped that language, you’re talking about an ongoing tightening of policy, which is much softer language. I’m not quite sure why.”

Carney’s follow-up response was even more convoluted and evasive.

It is a tough situation for everyone. Yet, by now, the audience should fully understand that the Bank of England is heavily biased toward a very slow and reluctant crawl toward higher rates: “It’s at a gentle pace, they’re limited and gradual moves, but that’s the core message.” In particular, the Bank will be much quicker to justify a need for low rates and rate cuts than a rationale for higher rates. This orientation should make anyone steadfastly skeptical anytime the BoE talks about higher rates. The BoE maintains a general conservatism born from a desperate desire to avoid triggering the next financial downturn especially with uncertainties still looming from Brexit.

Ahhh, poor Mark Carney. Remember when he appeared to be a genius running the Bank of Canada through the Great Recession? Has he lost his mojo now that he’s running the rather more messy Bank of England?

Yeah. He did a great job at the Bank of Canada. The UK is a bigger and more complex economy and did worse in the Great Recession than Canada did. If Carney were still at the BoC, he might just as clear as the current leadership.