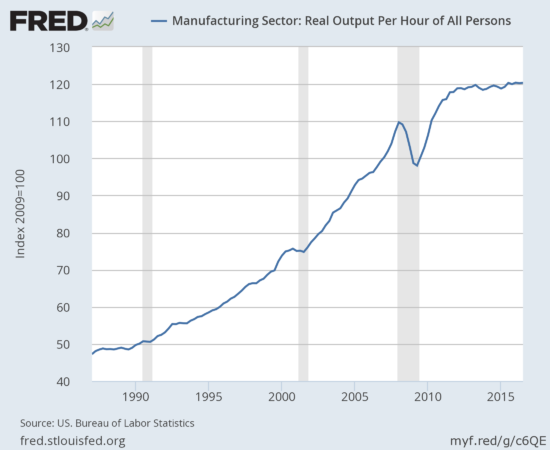

President-elect Donald Trump made a strong promise to bring back jobs to the U.S. from overseas. Manufacturing employment was a particular showcase in this campaign pledge. There are a lot of reasons to believe that a to return jobs to the U.S. will be extremely hard to accomplish. I am particularly struck by the data on the health of manufacturing in the U.S. First of all, the productivity of American manufacturing workers, as measured by real output for worker hour, is better than ever. However, that productivity has stalled through most of the economic recovery. The stagnation stands in stark contrast to the soaring productivity that characterized American manufacturing from around 1990 to 2007 and then again in the first years of the current economic recovery.

Source: US. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Manufacturing Sector: Real Output Per Hour of All Persons [OPHMFG], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, December 10, 2016.

The lack of productivity gains acts as a drag on the attractiveness of American manufacturing. To the extent other countries experience strong productivity gains, those locations may increase in attractiveness all else being equal…even beyond simple wage differentials.

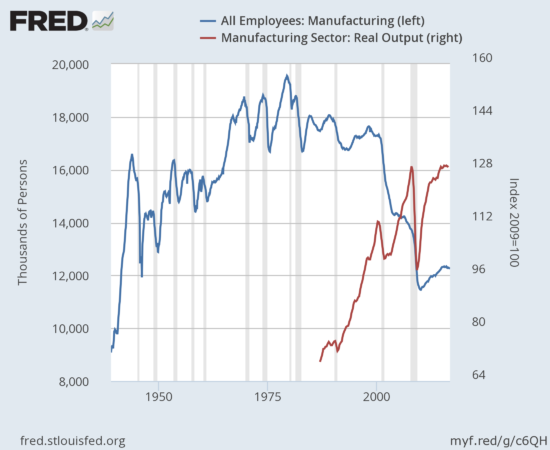

Even more interesting is the level of manufacturing employment versus real manufacturing output. The level of employment in manufacturing reached an absolute peak in 1979. From 1966 to 2001, manufacturing employment bounced within a tight range from around 17.1 million to 18.8M, just below the 1979 peak of 19.6M. After 2001, employment took its “final” plunge and never came back. YET, real manufacturing output continued to soar going into the last recession. After the recession ended, real manufacturing output soared all over again as employment made the slightest of recoveries. In other words, America’s manufacturing muscle as measured by output is relatively healthy. However, a lot fewer workers are needed for this output. Technological advancement, not foreign competition, is likely the biggest culprit of this dynamic since jobs sent overseas cannot contribute to America’s manufacturing output.

Source: US. Bureau of Labor Statistics, All Employees: Manufacturing [MANEMP], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; December 11, 2016.

In other words, to make a serious dent in manufacturing employment Trump will most likely have to figure out how to increase the productivity of manufacturing workers faster than the productivity gains of the technology that reduces their employment. Government is probably the wrong place to figure out how to pull off such a marvel.

There are of course minor victories to be had in forcing companies to change existing plans to ship jobs overseas – as in the now famous case of Carrier, a unit of United Technologies (UTX) – but resurrecting jobs that are now lost to technological advancement will be next to impossible. Even the math of saving existing jobs does not quite add up as expected as expressed by the disappointment of some Carrier workers (see “Carrier employee: We feel lied to“).

At this point, Trump’s administration would do well to focus on somehow cranking up the engine of innovation: an expansion of types of products, more businesses, and bigger GLOBAL markets. What has been lost is mostly gone. What can be gained is somewhere in the future of American ingenuity.

Full disclosure: no positions