According to “Building a Better America One Wealth Quintile at a Time” by Dan Ariely and Michael I. Norton, Americans are generally misinformed about the true distribution of wealth in America. Robert Reich’s “Aftershock: The Next Economy and America’s Future” represents an insightful and creative approach to educating the reader on income inequality and potential ways to address the issue.

The concept and topic of income inequality becomes an increasingly urgent topic the longer the economies of the developed world struggle to reduce unemployment rates even as large companies retain record profits. My first in-depth introduction to the economic principles of income inequality came from reading Robert Reich’s book. It was an eye-opening experience. I am also glad I waited over a year to write a review of the book. Since reading Aftershock, I have discovered valuable insights from other economists with different viewpoints that have further refined my own understanding. For example, while I accept that income inequality exists and is at unacceptably high levels, I do not think a coordinated, sinister process has produced these conditions. This interpretation means that I favor structural solutions like improving educational opportunities over distributional solutions like direct income transfers.

In this review, I provide a highlight summary of “Aftershock” and then an in depth exploration of some of its topics. I end with a sampling of other economists and related researchers who have developed differing conclusions from studying income inequality.

Highlight Summary

Robert Reich reviews America’s history with income inequality and how it helped to weaken the economy going into the Great Depression and the Great Recession. He is inspired by Marriner Eccles, chairman of the Federal Reserve Board from 1934-1948. Eccles concluded in his memoirs that the Great Depression was caused by the increased concentration of wealth which reduced the purchasing power of everyone else. This process compromised the ability for consumers to purchase enough of the economy’s (potential) output to sustain growth:

“As mass production has to be accompanied by mass consumption, mass consumption, in turn, implies a distribution of wealth – not of existing wealth, but of wealth as it is currently produced – to provide men with buying power equal to the amount of goods and services offered by the nation’s economic machinery…as in a poker game where the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped.” (p17-18) – Eccles, 1950

Reich describes how a restoration of balance helped drive America’s post-war prosperity. He also warns that a future of persistent income inequality has the potential to fuel a reactionary political movement that seeks to punish the rich even if it further worsens the economy. Reich concludes with a substantial list of recommended solutions that almost all rely on government intervention and income transfers. Even as Reich occasionally resorts to moralizing and dipping into the well of “American values,” he exerts considerable effort on presenting data (although sometimes poorly referenced or incomplete), pragmatism, and a holistic view of the economy.

The following three quotes from the book effectively demonstrate Reich’s core premise and principles:

“The fundamental problem is that Americans no longer have the purchasing power to buy what the U.S. economy is capable of producing. The reason is that a larger and larger portion of total income is going to the top. What’s broken is the basic bargain linking pay to production. The solution is to remake the bargain.” (p75)

“If the underlying ‘fundamentals’ are in order; if consumers are subsequently capable of spending and saving; if businesses have good reasons to invest; if governments maintain a fair balance between public needs and fiscal restraint; if the global economy efficiently allocates savings around the world, and if the environment can be sustained – then we can expect healthy and stable growth. But if these conditions are out of whack, economies as well as societies become imperiled.” (p5)

“Unless America’s middle class receives a fair share, it cannot consume nearly what the nation is capable of producing, at least without going deeply into debt. And debt on this scale is unsustainable, as we have seen. The inevitable result is slower economic growth and an economy increasingly susceptible to great booms and terrible busts….Widening inequality, coupled with a growing perception that big business and Wall Street are in cahoots with big government for the purpose of making the rich even richer, gives fodder to demagogues on the extreme right and the extreme left. They gain power by turning the public’s economic anxieties into resentments against particular groups…such demagogues and the movements they inspire can cause great harm.” (p127)

In-Depth Review

I like to use a thought experiment to anchor my understanding of Reich’s core economic principles. Imagine a world where ALL the owners of production pay ALL production workers subsistence wages (like a feudal system). As long as workers can access debt (likely securitized so that the owners of production can “invest” in it), they can buy more than just food, water, and shelter. With exceptionally low costs and high revenue potential, owners can make massive, out-sized profits. However, as soon as the bills come due, the entire unbalanced scheme collapses as workers find they have insufficient income and/or savings to even service this debt. After all, debt is a claim on future earning power, and workers need those future earnings just to maintain subsistence living. Production grinds to a halt as demand evaporates in a flash. The market of production owners is too small to keep all the factories humming.

Now, imagine moving wages somewhere above subsistence. This is akin to the owners of production investing in the real consumption power of their workers (rather than their debt). These higher wages translate into greater purchasing power just as debt did, but it is actually sustainable (affordable). The higher the wages, the more production that can be purchased beyond subsistence living (not including any price adjustments that occur from increased demand). A cynic may of course lament that these higher wages come at the expense of profits and the incomes of the owners of production. However, I believe the economy as a whole benefits when the owners of production can still easily sustain a lavish and comfortable life while workers can now enjoy standards of living far above subsistence. Economic growth becomes sustainable, profits are sustainable, and economic prosperity is shared by a much larger proportion of the population. As the entire economic pie grows, workers can even dream about upward mobility based on their motivation and ability to increase their productivity.

On the surface, translating this thought experiment into today’s reality seems to beg for income transfers for establishing more economic equity. Reich anticipates the accusation of “Robin Hood” redistribution regarding his proposals for assisting low and middle-income families with taxes from corporations and the wealthy. He tries to focus on proposals that provide net benefits, at least in theory, for everyone: wealthier and more secure workers who can support the profitability of companies.

I am positive that vigorous arguments can ensue over Reich’s approach since it leverages the work of economist Maynard Keynes by presuming that the government must intervene to re-balance an economy where incomes become overly concentrated. While economists will never agree about the proper role and levels of taxation and government benefits, at a minimum, I think the spirit of Reich’s structural proposals can garner widespread appeal. I also acknowledge that the difference between a structural solution and an income transfer can be one of opinion and ideological bias. From an implementation standpoint, a large challenge for massive government programs is the equally massive compromise required amongst opposing politicians and special interests that create loopholes and special conditions. Reich does not account for these costs in his proposals even as he lambastes a similar failure in the Obama administration’s health care legislation.

I have categorized Reich’s proposed solutions below. To simplify the presentation, I do not include his dollar figures for estimated costs and benefits:

Income transfers to workers

A reverse income tax: Add money to worker incomes, essentially increasing the income ceiling for the Earned Income Tax Credit. Lower tax rates above this threshold up to another ceiling.

Medicare for all: Every American can sign up for Medicare with subsidies for low-income and middle-class families. Reich argues that this system will be more efficient and reduce costs for everyone.

Income transfers directly from companies and the rich

Carbon tax: Tax coal, oil, and gas based on the amount of carbon contained in the fuel. Reich acknowledges this will increase the price of many products, but he does not offer a direct estimate of whether the benefits of a carbon tax outweigh the additional costs to consumers.

Higher marginal tax rates on the wealthy: Includes treatment of capital gains as regular income.

Severance tax on corporations: Profitable companies pay a tax for each fired worker.

Structural solutions

A re-employment system: workers who lose a job and take one with a lower pay can receive some portion of the lost pay for a period of time (like wage insurance). Reich assumes that wage insurance provides incentive to take any available job, but I can imagine it could also provide an opportunity for short-sighted individuals to take an “easier” job while getting compensation commensurate to a harder job until the wage insurance ends. Unemployed workers receive income support for training and education. (It was not entirely clear whether this re-employment system completely replaces unemployment or whether it is additive. I think that unemployment benefits must be reduced to make wage insurance work better).

School vouchers based on family income: Replace pubic school spending with vouchers that decrease in value the higher the family income. Interestingly, this system could induce public schools in wealthier areas to compete for students in poorer areas since the vouchers of the rich would not be enough to cover costs. Cynics could also imagine these schools shutting down rather than compete.

College loans linked to subsequent earnings: Make tuition free at public colleges and universities and provide loans for those students who choose private education. Graduates pay for their education and/or their loans by sending a portion of their earnings for a certain number of years into a fund that finances this system.

Make public goods free of charge: Make free and increase the availability of public transportation, parks and recreational facilities, museums, and libraries. Reich argues that these measures create jobs and dramatically improve the quality of life.

Remove money from politics: Establishing a “blind trust” is Reich’s most significant proposal here. Theoretically, a blind trust prevents candidates from knowing who contributed to their campaigns and prevents them from legislating according to the dictates of their paymasters. Reich hopes to curb the dominant influence of the super-rich, especially in the financial sector which grew to an unhealthy proportion of the economy.

Except for the proposal that supposedly reduces healthcare costs, Reich does not generate any ideas that help companies reduce costs and subsequently increase their ability to pay workers. In fact, Reich will increase operational costs, putting more pressure on worker productivity to compensate. In particular, companies could cope with the severance tax by either reducing pay and benefits to account for the increased labor costs and/or reducing or slowing hiring as much as possible in order to limit severance costs.

Of course, no one can know the optimal distribution of income amongst workers and the owners of production. My thought experiment suggests that an economy cannot function well when sub-standard pay prevails. An educated and highly skilled workforce should command the better pay for production that is part of sustaining a functional balance. When the economy crumbles coincident with increasing income inequality, the trauma certainly seems to highlight the importance of income equity. However, income inequality is not a necessary condition for an economic slowdown. Here is Reich’s case for correlating income inequality and economic calamity:

Reich’s three stages of American capitalism:

- 1870-1929: increasing concentration of income and wealth

- 1947-1975: more broadly shared prosperity

- 1980-2010: increasing concentration of income and wealth

At the end of each period of increasing concentration of income and wealth came economic calamity, the Great Depression and then the Great Recession.

“In the late 1970s, the richest 1 percent of the country took in less than 9 percent of the nation’s total income…By 2007, the richest 1 percent took in 23.5 percent of total national income. It is no coincidence that the last time income was this concentrated was in 1928.” (p6)

Reich claims that if the economic gains of the past 30 years were more equally distributed, the average person in 2007 would have been about 60% better off. That change represents a lot of extra buying power in the hands of a lot of people. Instead, wages stagnated; for example, the median male wage of $45,000 is lower than thirty years ago when accounting for inflation. (Reich does not attempt to account for changes in benefits).

Reich explains that this income concentration does not directly cause financial implosions. Instead, increased concentration forces those in the majority to increasingly rely on debt to achieve aspirational living standards. Without the income to sustain this spending, the subsequent decline in spending plunges the economy into trouble.

So what happened to drive the increasing concentration of income and wealth? Reich decries a tax system that favors the rich, deregulation, and reduced support for the safety net. The government did not enforce the “basic bargain”:

“Starting in the late 1970s, and with increasing fervor over the next three decades, [government] deregulated and privatized. It increased the cost of public higher education, reduced job training, cut public transportation, and allowed bridges, ports, and highways to corrode. It shredded safety nets – reducing aid to jobless families with children, and restricting those eligible for unemployment insurance so much that by 2007 only 40 percent of the unemployed were covered.”

As a result:

“…anything that’s desirable but in limited supply has become less accessible to the vast middle class as purchasing power has come concentrated at the top. And as the rich have simultaneously withdrawn from institutions dedicated to the common good, like public schools, they both bid up the price of desirable private ones and reduce the quality of what remains public.” (p99)

Reich’s chronology implies that in 140 years of American capitalism, ONLY 28 of those years featured both a balanced income distribution and general economic prosperity. Even so, these 28 years still featured the economic marginalization of large segments of the population. So, the nirvana of income equity and shared prosperity must be quite difficult to achieve! This reality serves as a strong caution about the true costs that could be involved in rebalancing the economy.

Perhaps part of the difficulty comes from the costs involved and the political will required to establish and support the related initiatives. For example, Reich is a big fan of the government-sponsored safety net because it enables consumers to save less to cover life’s risks and spend more on the economy’s output. In other words, this system pushes a greater portion of wages into consumption. Unfortunately, economists and politicians have now argued for decades, without conclusion, about the balance of costs and benefits of this trade-off.

In China, high savings rates, used to cover the costs of personal safety nets, suppress consumer spending. Reich notes “the average urban household saves about 30 percent of its income, and the savings rate has been rising despite growing incomes and wealth.” The Chinese government seems to recognize its under-investment in its social safety net and is making small steps to improve the situation. China has recently doubled its spending on the social safety net to around 6% of the Chinese economy. Reich believes that until China boosts the safety net closer to the 25% level like other developed nations, China will remain heavily dependent on its exports to other countries. (Reich does not contemplate whether the sovereign debt issues in Europe are partially a result of overspending on this safety net.) While China’s production-oriented economy generates the jobs that millions of Chinese seek as they move from rural to urban areas, it does not generate the consumption that could replace the anemic consumption from developed countries.

According to Reich, Americans have scrambled to cope with the relative decline in their fortunes.

More women moved into the workforce bringing more income into the average household. Reich does not quantify how much of this change occurred as a coping strategy or as the natural consequence of more opportunities opening up to women. (Some of this additional income was spent on increased childcare costs).

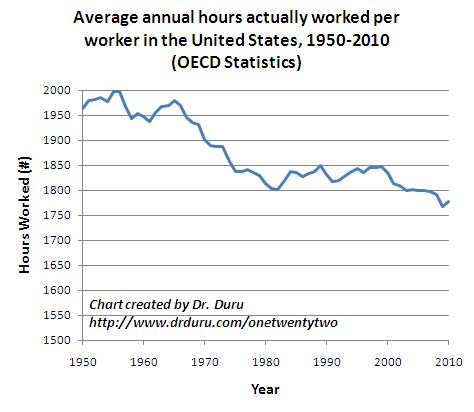

Reich claims Americans are working longer hours. Reich poorly quantifies this change as he provides the number of work hours per family instead of per worker. In fact, according to the statistics from the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), average annual hours worked per worker in the U.S. have markedly DECLINED since 1950. The steepest portion of the decline occurred from 1965 to 1980. Perhaps a large portion of the new entrants to the economy, women and ethnic minorities, acquired jobs that provided fewer hours than existing entrants. Regardless, after this transition, hours stabilized and did NOT increase during the time in which Americans were supposed to be increasing hours to cope with increasing income inequality. The further dip in recent years coincides with the Great Recession.

Source: OECD Statistics

The final coping mechanism was the drawdown on savings and increase in debt. The data here are well-established (for example, see “Collateral Damaged: The Marketing of Consumer Debt to America“). Before 1980, average household debt, including mortgages, ranged from 50 to 55 percent of annual after-tax income. By 2001, this share reached 100% and by 2007 it was a whopping 138%. Reich obliquely referenced particular actions by the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates, but these rates have experienced a secular decline since the highs of the 1980s. This decline alone could explain the growing disincentive to save. In 2007, I referenced the concurrent drop in interest rates and saving rates as “Undersaving Still Driving the Economy.” The collapse of America’s debt bubble brought the ride to a crashing halt.

Debt was the last leg of the stool propping up the average American consumer. If Reich’s characterization of income inequality is correct, average Americans from all political persuasions may begin to converge on one view that the game is rigged against them. The government has been more successful at propping up banks and corporate profits than the middle class and working people. With stagnant wages, a balance of power in the hands of companies and a few, and increasing state and local taxes, a rising tide against the rich could take hold, especially from the extreme left and extreme right:

“If nothing is done to counter present trends, the major fault line in American politics will no longer be between Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives. It will be between ‘establishment’ – political insiders, power brokers, the heads of American business, Wall Street, and the mainstream media – and an increasingly mad-as-hell populace determined to ‘take back America’ from them.” (p145)

Reich thinks that sooner or later, the CEOs of America’s largest companies and Wall Street will get concerned enough to act. Their profits will be constrained by the declining purchasing power of the American middle class, and the growing middle classes of emerging economies will not sufficiently compensate for this drop. The ability to conduct business as usual will be interrupted by the increasing anger of the general public toward “the establishment.” The political climate could start producing anti-capitalist legislation.

These change agents sound ominous, but they are likely inevitable if Reich is correct about the pressures building around income inequality. Rapid global economic integration over the last twenty years or so has abruptly shifted job growth to its cheapest sources, further squeezing the working classes in America (and other developed economies). According to John Nye of George Mason University, the first true globalization occurred in the late 19th century. By the 1920s and 1930s, a major backlash to this globalization spread across many countries. A similar process may now be underway (for more details see “Nye on the Great Depression, Political Economy, and the Evolution of the State” from the Library of Economics and Liberty). Time will tell.

Alternative perspectives on income inequality

Most of my exposure to alternative perspectives on income inequality have come from EconTalk at the Library of Economics and Liberty, podcasts hosted by Professor Russ Roberts of George Mason University. For anyone interested in developing a broad appreciation of the complexity of this topic, I highly recommend comparing and contrasting Robert Reich’s thinking in “Aftershock” to the ideas and research of Robert Frank, Richard Epstein, William Bernstein, Daron Acemoglu, Steven Kaplan, Bruce Meyer, and Tyler Cowen. Professor Roberts generally does a good job of interviewing and challenging his guests even when they agree with his own thinking. Roberts is a Libertarian who has recently begun to doubt the ability of the economics profession to separate ideological bias from its research. He recognizes that income inequality exists but questions how it is quantified. He is also highly skeptical that today’s income inequality in of itself has a direct impact on the real economy.

To encourage further exploration, I have included choice quotes from each podcast and a little editorial. Each synopsis represents what I found most important. Note that the transcripts provided with the podcasts are subpar because they are unstructured and do not identify the speaker. Finally, there could be other EconTalk podcasts relevant to income inequality that I have yet to consume.

—-

William Bernstein on Inequality (Oct 6, 2008)

Synopsis: Bernstein argues that relative status matters to people’s well-being. Roberts retorts that income inequality does not matter, and he challenges Bernstein’s empirical evidence.

Key quote: “When you have increased inequality, your costs of protecting property rights increase dramatically.”

Key challenges (from Roberts):

- “If we put a tax on doctors and lawyers, on argument that their services are overcompensated, or not fair, or that they are so much better off relative to others. Because of market forces, it raises their pre-tax incomes. Not dollar-for-dollar, but limited success in achieving final goal.”

- “Technology has enhanced the returns to having a scarce skill…In times when entrepreneurial opportunity is greatest you see a lot of fortunes made, mostly good, why is it viewed as some kind of a bad thing?”

Richard Epstein on Happiness, Inequality, and Envy (Nov 3, 2008)

Synopsis: Epstein and Roberts conduct a wide-ranging discussion on the moral, emotional, and economic behaviors that drive people to compete and cooperate for resources and success.

Key quotes:

- “Hayekian insight: if you subsidize farmers to minimize the fluctuations they experience, then all the fluctuations are borne by people providing the subsidies.”

- “Stoking the fire on envy will lead to a climate in which there will be long-term social stagnation. Safeguards weaker today than they have been. Gains from private rent-seeking activity are perhaps larger than they have ever been before.”

(Partial) Explanation of income inequality (Roberts): “Over last 35-40 years, measured inequality has risen in income distribution. Large increase in immigration, demographic change in the 1970s due to an increase in the divorce rate. Returns to education have risen, especially at the high end; entrepreneurial environment, small group of people earn high rewards.”

Robert Frank on Inequality (Nov 15, 2010)

Synopsis: Frank first started writing about income inequality with a book called “Choosing the Right Pond: Human Behavior and the Quest for Status” introduced in 1985. Frank proposes to replace the income tax with a steeply progressive tax on consumption. This tax reduces disparities in consumption and favors investment. Frank acknowledges that some income inequality must exist but after a certain point, income inequality reduces output. Moral issues also matter and economists should deal with them.

Key quote: “…it has become a slogan in American political discourse that it is illegitimate to tax the rich and transfer income to the poor. And in a democracy, if you don’t attend to the interests of the poor in an efficient way, you’ll just end up attending to those interests in a less efficient way. The problem with cost-benefit analysis: that’s got to be the standard if you want to make the pie as big as possible, adopt all the policies that pass the cost-benefit test; the problem you hear from champions of the poor is that you can’t use cost-benefit analysis because that gives an unfair advantage to the rich.”

Key challenge (from Roberts): “So the median person in the 1970s, you look at their standard of living over the last 30 years starting as a young person, not just from life-cycle effects which would always be there; but their standard of living is much higher. So I accept the point that the keeping up with the Joneses can be unhealthy; but I reject the argument that the median person is influenced by those rippling down from up above to pursue options they can’t afford. I think they can afford more; they’ve chosen often to spend it on housing and education, indirectly in the form of choosing where they live. Final point: it’s a bad system to have your school choice tied to where you live and we ought to get rid of that. Certainly does distort the housing market.”

Tyler Cowen on the Great Stagnation: (Feb 14, 2011)

Synopsis: “Cowen argues that in the last four decades, the growth in prosperity for the average family has slowed dramatically in the United States relative to earlier decades and time periods (specifically compares post-1973 to 1917 to 1957). Cowen argues that this is the result of a natural slowing in innovation and that we expect too much growth relative to what is possible. Cowen expects improvements in the rate of growth in the future when new areas of research yield high returns. The conversation includes a discussion of the implications of Cowen’s thesis for politics and public policy.

{My note: This podcast REALLY made me think, and I listened to it multiple times. I found so many quotes so compelling and thought-provoking. Thus, I have pasted a lot more quotes here!}

Key quotes:

- “If you look at median family income since 1973, it doesn’t even double. There are various ways of measuring it. Under one plausible estimate, from 1973-2004, it’s only gone up 20-30%. In the last decade, it’s actually declined. There has not been net jobs growth in the last decade. So, one can think of the Stagnation as coming in phases. Different starting points for different parts of it…Productivity statistics point us in the same direction. And statistics on education. And test scores. So, we have a bunch of different facts, which broadly speaking are independent, pointing us in the direction of a slowdown of some kind.”

- “At all levels of government, including state and local. Add those all up, take out the overlap, and it’s a pretty big chunk of the economy, like 20-30%. Those are all sectors where there are massive subsidies, massive distortions of incentives, a lot of bad policy; and it’s hard to measure value. So, when we talk about biases in measuring output and living standards, the bias I worry about the most is we’re spending a lot of money and simply writing it down as value added when it might not be.”

- “I think the Internet has a few implications. One is that it has made capital more substitutable for labor. This has helped people like you and me an enormous amount; we have not seen a great stagnation. People who I called Infovores in a previous book have had phenomenal increases in our well-being; and that includes the two of us. The benefits are smaller I think for the median American. If you look at the biggest Internet-based firms, like Facebook, they employ remarkably small numbers of people…in terms of job creation, median income, there has been a change in the distributional pattern itself, at least over the last 10 years–less geared toward the median and more geared toward Infovores and the top 10%.”

- “One trend I’ve seen–I don’t think it’s the main driver of the stagnation–but there is an awful lot of innovation in rent seeking in lobbying, in moral hazard, financial sector playing the ‘heads, I win; tails you lose’ game…If you look at a graduating class from Harvard, I think it’s striking how many of the smartest, most ambitious ones want to go into finance. I don’t think that’s healthy.”

- “I think the Great Stagnation would be much easier to live with, and we would be much happier with it, if we had better fiscal policy and simply a better realization at the political level that politics can’t do everything; the President can’t always fix the economy; we are not going to grow at x% every year; that we really do need fiscal discipline and a sense of limits. And if we had that–and you and I know we don’t; we are not close to it from either party–the Great Stagnation would be much less of a worry. Part of the problem, a big part, is simply we are not psychologically equipped to deal with this slowdown.”

- “I think when you improve policy there is always going to be the question: Is this improvement a one-off change–which is fine, I’m all for a one-off change–or will it improve the long-term rate of growth? You’ll find economists from all points of view pretend to know: this will be a one-off change or will improve growth. In most cases, we don’t actually know. We should institute as many policy improvements as we can. We won’t know in advance which ones will improve the growth rate and which ones will just give us one-off improvements; and do them all, and let it all kick in and see how good it’s going to be. That’s my basic attitude.”

- “Politics has become uglier, stupider, more polarized for the most part. I’m somewhat pessimistic there. I don’t see a path toward it improving, but if you look back toward the history of the American republic, politics, especially in the 19th century has been very partisan, polarized, and stupid, based in lies. So, it’s not an innovation; actually something quite old. I think we’ll manage to survive it. What I do see is more smart people than ever before; and they work really hard, and they want to innovate. That absolutely is true of 2011; big reason to be optimistic.”

Daron Acemoglu on Inequality and the Financial Crisis (Feb 21, 2011)

Synopsis: “Acemoglu suggests…the financial sector through its political influence distorted the rules of the game, benefiting executives in the industry, which in turn led to outsized rewards and ultimate instability in the financial industry.” Acemoglu draws a distinction between labor inequality, which is well-understood, and top inequality, which features income skew at the top 1% and 0.1% and is not well-understood because of limited data. The discussion launches from Acemoglu’s review and critique of “Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy” by Raghuram Rajan. Acemoglu disagrees with Rajan’s premise that politicians have been responding to the discontent of the lower or middle parts of the income distribution. Instead, Acemoglu insists politicians have been responding to the lobbying and campaign contributions by people who are already extremely rich and very well-organized. Reduced political competition has compromised the ability of the political system to check these influences. Acemoglu is optimistic about the prospects for fixing the system given the U.S. still has strong institutions and relatively low levels of corruption compared to the rest of the world. Acemoglu cites numerous studies and research for his data and also points out areas where more data and research are needed.

Key quotes:

- “The general consensus is that [technological change] combined with perhaps slower increase in skills in the last 20 years or so than the United States had experienced before led to a sharp increase in the college premium and a sharp overall increase in the overall inequality of the labor market.”

- “…if you look at the gaps between the 90th and 10th percentile, that has sharply increased in the 1980s, and sort of stabilized in the 1990s; increased again in the late 1990s and so on. In line with historical trend. What’s going on with the top inequality is rather remarkable and we probably haven’t seen anything to this extent…starting in the 1970s, there is a remarkable explosion in the wages in the financial sector relative to the rest of the economy.”

- “…there was a political process that led to certain types of distortions in the financial industry. Those distortions then both laid the seeds of the financial crisis–because they encouraged the wrong type of risk-taking–and also in the process made a lot of money for those people taking risks while those risks still hadn’t turned south yet.”

Roberts’s pet peeve: “But on Wall Street, what has happened in the last 25 years is that if you do really stupid things and you lose a lot of money for your firm, you keep going. You make a lot of money, hundreds of millions of dollars sometimes–as an individual. Even though you’ve destroyed your company. And you can stay in the game. So, something is drastically wrong. And you are doing it not with your own money, but with other people’s money. The question is why would people continue, give them money…But on Wall Street, you can keep getting money for a while, from you and me, the Fed helps you out. It’s clearly disastrously inefficient.”

Bruce Meyer on the Middle Class, Poverty, and Inequality (Oct 3, 2011)

Synopsis: Current measures of income inequality do not properly take into account inflation or post-tax income. If they did, we would find significantly less income inequality than conventional wisdom claims. When measured using the Boskin commission’s assessment in 1996 that the inflation rate (CPI) is over-estimated, consumption and median post-tax incomes have increased 50% since 1980.

Key quotes:

- “The changes in the types of families that are in the United States over time don’t play a big part in the changes in median incomes or poverty over time though you can see an effect of increased education, particularly if you look at measures of consumption because consumption seems to be a little more closely associated with improved education than income is…What we do see is that there are groups that have had their poverty decline much faster than others, so those households that are headed by someone 65 and older have had their poverty decline much faster. That’s also true for single-mother-headed households. On the other hand, married couples with children, their poverty rate hasn’t declined as fast as other groups. And that’s even more true if you look at their spending patterns, at what they are consuming rather than their income.”

- “…the official income measure says that poverty has gone up over the last 10 years…over the longer term looking at other measures like the types of housing people live in, the types of cars they drive, it suggests that people at the bottom have seen an improvement in their living standard over the long term.”

- “When you look at people near the poverty line, they are not doing a lot of borrowing. So, debt is not a big part of the increase in consumption at the bottom. For the median I think that’s more of a real issue. You can see that in the last couple of years consumption has gone down, as people have had to pay back debts.”

- “What we find is that in the last 30 years, there was this period in the 1980s where there was a very big increase in inequality no matter how you measure it. Whether you look at income, consumption, pre-tax or after-tax income, the late 1970s and early 1980s were bad for inequality. But since then, the picture, when you measure things better, when you look at after-tax income or better yet when you look at consumption, things aren’t that bad for bulk of the population. So, the difference between the 90th percentile and the 10th has grown a little bit over time since the late 1980s but not a lot. And if you look at the bottom half of the distribution, the 10th percentile relative to the 50th, the 10th has grown relative to the 50th over that period of time.”

- “There’s been some work on the increase in inequality, and a fair amount of it has been attributed to changes in the demand for high-skilled labor and the failure of us to supply enough high-skilled labor at the times when demand for it was increasing. There are also other stories. Around that time there was little increase in the minimum wage, which can decrease inequality in certain circumstances…And at that time we also had very high inflation.” (the late 1970s and 1980s)

Roberts’s revenge: “The top 1%–a lot of them are entertainers, movie stars, sports figures–people who have been able to leverage their skills in dramatic ways because of improvements in technology and they are more valuable than they used to be; which is just fine with me. It includes people who are great entrepreneurs. It includes people who earn money because they are being subsidized. Our industry, education, is highly subsidized in direct and indirect ways. When I get depressed about Wall Street, I am slightly consoled by the fact that the subsidies to borrowing and lending on Wall Street by large financial institutions increase the demand for academic economists; and you and I are probably the beneficiaries of that. I’m not proud of it, but it helps me sleep better at night.”

My editorial: This podcast is the weaker one of the bunch, but I included it for completeness. The least convincing claim is that hedonic adjustments to inflation have caused over-estimation of the inflation rate. Numerous economists and pundits alike have stated the exact OPPOSITE claim; that is, the government’s CPI (consumer price index) UNDER-estimates the real rate of inflation. Moreover, Meyer has nothing to say about the top 1% of incomes. He is entirely focused on the median which can move upward even as the distribution above the median gets more and more skewed. Some of the key quotes here were interesting because they directly contradict some firmly held assumptions and convictions of Professor Russ Roberts.

Steven Kaplan on the Inequality and the Top 1% (Nov 7, 2011)

Synopsis: “Drawing on work with Joshua Rauh, Kaplan talks about the composition of the richest 1% and 1/10 of 1%–what proportions come from the financial sector, CEOs from non-financial corporations, athletes, lawyers and so on. Then he discusses how the incomes of these different groups have changed over time. Kaplan argues that these groups have increased their incomes by similar proportions, suggesting that a failure of corporate governance is not the explanation of rising CEO pay.” Kaplan and Roberts debate the sources of the financial crisis and whether misaligned incentives had anything to do with the problems.

Key quotes:

- “…in 2009 the top 1% I calculated at 17.6%. I’ve seen other calculations a tad under 17%, but it’s basically gone from 23.5 to 17. What’s interesting about 17 is that inequality in 2009 is actually lower than it was during any year of Bill Clinton’s second term…I like to stop at 2000 because this is was the last year of Bill Clinton’s term. It was also the last year before the 2001 recession. A mini-peak. There the top 1% had 21.5% of income and the top .1% had about 11%.

- “CEOs were just not unusual…their pay went up but it more or less over time went up like the rest of the top 1% or top .1%. So, this a view that corporate governance is broken, that boards are corrupt seems hard to understand when the CEOs are going up just like all the others.”

- “technology allows talent to scale; you see that in entertainment–with cable, which allows you to segment your audience and actually now gets more product to more people–that allows talent to scale. For lawyers, you are applying your talent to bigger deals. Technology has been very important, and it’s been information technology which has really helped people scale. The second piece is globalization; and again, it allows you, if you are an investor you can invest not only in the United States but globally; if you are a corporation you can invest globally–it’s allowed companies to outsource and that also allows talent to scale.”

-

“I think that first of all the view that bankers did heads-I-win, tails-you-lose and that they thought that way, I think just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense…after tax, they might have ended up with nothing but they certainly ended up with far less than you’d give them credit for given pre-tax.” (Roberts point out the following: “That’s not the way Jimmy Cayne tells it in House of Cards

, by William Cohan. He’s interviewed in there, and he says: Well, I lost a billion, which is tough on my heirs; but he says he’s left with half a billion.”)

Roberts’s Pet Peeve: “…when that share fell from 23.5 to 17 over the 2007-2009 period, that wasn’t good news for the rest of us in the 99% because our incomes also went down. Theirs just went down a lot more…As an economist I find it deeply annoying, and especially when economists do it–income is not a [zero]-sum game. Somebody else’s income does not come at your expense. It could…”

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: Seeking Alpha provided this book for free in exchange for a book review

Wow, great piece and given its depth, breadth and references it must have been quite a labor (of love). In the larger context of Obama’s coming class warfare approach and the Occupy people, it’s quite a timely piece.

Most of my more salient reactions to the references’ ideas revolve around big picture issues such as the absolute standard of living of the 99ers and those below the poverty level. Yes I believe the inequalities are enormous (don’t really care if they have increased a few percent lately). And as a psychologist I recognize as long ago proven, one of the reference’s points about feelings of inequality being based on relative comparisons rather than empirical absolute facts. In the heydays of Getty, Rockefeller, Carnegie or Vanderbilt, the masses did not see nor rarely hear of the inequalities. Now they are bombarded with it. Yet everyone has a 50 in. plasma and a smart phone, the latter ubiquitous even among those unemployed Occupy people. Moreover, the government spends $62k for every family of 4 under the poverty level (see http://www.forbes.com/sites/peterferrara/2011/04/22/americas-ever-expanding-welfare-empire/) . So I think there are very few out there that don’t have a decent place and 3 squares. That might sound heartless but it’s clear to me that everyone was not created equal and so the less ambitious, intelligent or talented will as a group never fare as well as their counterparts, in a capitalist society.

Don’t get me wrong by thinking I’m part of or subscribe to the ideas of those that Acemoglu refers to when saying that “politicians have been responding to the lobbying and campaign contributions by people who are already extremely rich and very well-organized.” I think that is obvious on the part of the politicians, yet the times they are a changing. Take the Middle East. It’s a harbinger of how the 99% will get it together – social media. Yes I know social media is everything these days but you have to admit that tweeting is generally highly trusted, especially that of those we follow. Facebook will contribute also.

Moreover, the seeds are there upon which to build such a movement. Who among your references is correct about income inequality is not as important as whom the 99ers believe is correct. And while there is probably a moderately high correlation between income and belief in inequality, the income distribution is highly skewed resulting in the overwhelming majority being believers in inequality.

Then there are those who may have comfortable incomes but think here and there the system is rigged. For example, many, me included, think the high-frequency traders have an unfair advantage that given the existence of an SEC is incomprehensible (till you remember the SEC is government workers). Many of those are coming to think that a “millionaire’s tax” is justified (even the polls show that idea has high attractiveness among rank and file Republicans). Throw in a bit of self-interest and you have a much larger potential set of members of a 99er coalition. The self interest often stems from the realization that hey, yeah I make $x00k. But the new xyz taxes won’t hit me. On the contrary, in the long run they may lessen my tax burden.

It will be interesting to see how this all plays out. Glacially I suspect.

Thanks again for sharing.

Best regards.

P.S. Your article is not showing up anywhere on SeekingAlpha that I can see.

Thanks for the detailed response! Writing this was indeed a labor of love. I “had to” do it because of my commitment to SA in getting the book for free, but also this is a topic for the ages. Writing this helped me get a much more comprehensive and deeper understanding of the various perspectives and approaches. I am not sure whether SA will publish it, but I informed them that this was written as part of my deal to write a review (albeit LONG overdue!). So, we’ll see. I posted it on my site because I want to be in complete control of the content in case, for some reason, any further editing needs to be done or I want to expand it later (and provide a link in this piece to another piece).

Anyway, to be clear, “fixing” income inequality is not about leveling out everyone’s income. It is (or should be) about making sure everyone has the opportunity to succeed to their best ability AND making sure folks are getting paid enough for their work that the overall economy can be self-sustaining. And yes, the devil is in the details!

I share your optimism that this will get worked over time. I think the convergence of the 99% awakening around the globe, the middle class getting more active and energized, AND some well-heeled individuals realizing that their money is better spent investing in their people and their country rather than sitting with the Nth hedge fund trying to make that extra million or two. 🙂

It will be glacial. Especially for anyone who wants everything fixed now. Just trying to roll out Reich’s proposals, assuming such a thing made sense, could take several Presidential administrations to accomplish, especially because of all the time it takes to debate, argue, compromise, implement, fix, and re-implement!

Thanks again for the feedback.