Several months ago, I had the opportunity to “talk shop” with a truck driver who specializes household moves. I will call him “Bob.” When Bob discovered that I write a blog dealing with trading and investing in financial markets, he asked me for my forecast for the economy. I did not have anything good to say for the near-term prospects in the moving industry, but I think he had the more interesting story to share. I quickly became fascinated enough with the industry’s dynamics to write this piece about movers. In doing so, I am reminded that, even in a time of record corporate profits, this country still has important parts of its economy that are struggling to survive. These are industries where numerous workers are struggling as if the recession never ended – revenues are not keeping up with costs and stagflation feels very real.

I asked Bob a series of questions, including some correspondence over email. Here is a consolidated summary of his responses…

Structure of the Moving Industry

The moving industry has a basic structure consisting of three major players: carriers, agents, and drivers.

Carriers have hauling authority. They also wield the ability to set prices (through agents) and assess chargebacks on the driver. Carriers are supposed to follow regulation 376.12, from the Federal Motor and Carrier Safety Administration, to determine leasing agreements. The regulation covers every aspect of leasing including: the specification of duration, compensation, and items in the lease; payment period; documentation; chargebacks; insurance; and escrow funds. Bob claims that carriers frequently fail to follow these rules or try to pass blame back to the agents, but paragraph “M” of the code makes the carrier responsible.

Agents book and pack the moves, supply labor, and control pricing.

Drivers haul goods from origin to destination, handle the unpacking, and sometimes the packing. Drivers are at the bottom of the food chain given they must accept the pricing set by carriers and/or agents. Drivers are all treated as contractors. Most drivers incorporate for tax reasons.

Pressure on Profits

The are enormous pressures on profits. Over the last 30 years, rate discounts have squeezed the topline by effectively negating rate increases. The pay rate for labor to load and unload goods has increased from around $10/hour to over $20/hour. Insurance costs have increased. Food prices have increased (more important for longer hauls). Yet, drivers are still earning no more than $50 per CWT (hundredweight: 1CWT = 100 pounds in North America), the same rate they were making in 1985. Bob provided many vivid examples of the difficulties involved in making money in his line of work.

In 2003, a class action antitrust lawsuit was filed against the household goods shipping industry. According to the settlement, “the lawsuit is about the assessment of fuel surcharges on certain interstate shipments of household goods. Plaintiffs allege that defendants set an inflated price for fuel surcharges charged to shippers for those shipments under a tariff named Tariff 400N.” Essentially, the lawsuit claimed that the fuel surcharge was making money. In Bob’s opinion, this was not a bad aspect of the surcharge since there has not been an actual increase in transportation rates since 1985. The carriers settled (Bob said “caved in”), and the surcharge was reduced by 15%, with no other increase to make up the difference. Bob explained that the surcharge was to cover costs above $1.17 per gallon. In 2003, the lawsuit was filed and settled with refunds going out. However, the threshold was eventually raised from $1.17 to $3.00 with no other mechanism for recovering the lost difference. This reduction in the fuel surcharge cost Bob $45,000 last year.

Third party brokers are also grabbing pieces of the shrinking revenue pie. They own no trucks but book a move and contract with the carriers. Bob thinks these movers are proliferating, but he also blames his industry for allowing these players to move into the business. They tend to take 15 to 20% of collected charges.

Disreputable movers are pressuring rates. These “scam” movers quote low numbers, sometimes below cost, complemented with fine print that generates much higher final prices. Some of these movers do not even own trucks.

Regulatory Pressure

New safety laws represent Bob’s latest pain. Some drivers feel compelled by economic pressures to postpone and delay maintenance and regular repairs. Thus, safety does get compromised. The additional safety regulations threaten to push drivers over the edge by substantially raising costs. Drivers who shirk these laws lose dearly if they get caught. Bob also feels that every truck scale he visits implements more scrutiny than ever, as if inspectors are searching for excuses to issue fines.

Pressure from Carriers

Carriers find all sorts of ways to charge back fees and costs to drivers in a process Bob describes as transferring income from the pockets of drivers to the pockets of carriers. For example, in 1983, an 18% fuel surcharge was charged to help pay for the high cost of fuel at that time, and the surcharge was delegated to the “transportation unit.” The moving companies of America then chose to roll the fuel surcharge into the tariff as a transportation rate increase. This change allowed them to claim half of the fuel surcharge away from drivers.

In a recent example, Bob complained about his carrier charging back for tickets above and beyond what the state scales charge the driver. Clearance lights sit on the top edges of a trailer. Low trees knock these lights down all the time, and it can be weeks before a driver can find a mechanic who can get high enough to fix these lights. The Department of Transportation is assessing major fines for these violations. In the time it takes for a driver to find an equipped mechanic, the driver runs the risk of getting a ticket that costs as much as $500. The carrier will charge a driver a separate safety chargeback while not including the details for that chargeback in the lease agreement. Yet one more problem bedeviling Bob. (See regulation 376.12).

Tariff 400N

Tariff 400N was purportedly established to include compensation for “long carries” (a moving job where the distance from the moving truck to the door of the building getting is greater than 75 feet) and “stair carries” in origin or destination fees for particularly challenging locations or expensive routes (“Item 135 charges”). While this tariff was eliminated, Bob explains that the carriers just changed the name of their tariffs and filed the terms from 400N. In 2003, the Household Goods Tariff Bureau (HHGTB) and the carriers decided to roll the driver’s cost-based extras (a small percentage) into Item 135 charges. Moreover, transportation charges were increased 3.8% to help compensate drivers for the long carries and stair carries removed from the new tariff. However, Bob complains that the transportation companies take half of this 3.8% increase. This is part of a process of transferring money from the driver’s “accessorial charges” into the transportation charge, effectively decreasing compensation for drivers to the benefit of the transportation company. (Accessorial, or additional services, are services such as packing, unpacking, or a shuttle service).

Bob provided a specific example of how this process works. Under the old tariff, a 10,000 pound shipment from South Beach, FL to San Diego, CA with many long carries and an elevator at origin, paid the driver over $1,000 extra for those two services. Bob could not get into the complex before 9:00 a.m. to start the job, and he had to leave by 4:00 p.m. He had to hire six men in order to meet this tight window. Normally, he would only need two men for a 10,000 pound shipment. The total labor cost came to $800, about $533 in lost profit for Bob. Under tariff 400N, only $73 of the extra $1000 goes to Bob, effectively a $927 pay cut and a big loss given the labor costs.

A Tough Way to Make A Living

Here are some representative examples to further demonstrate the difficulties in making money being a driver in the moving business:

- It takes 12 comparably sized shipments with no long carries or stairs to break even.

- It takes 240,000 pounds to load and deliver to break even.

- It takes just over 2 months of loading and delivering 112,000 pounds per month average to break even.

- One 10,000-pound shipment with excessive long and/or stair carries generates break even profits.

Last year, of 78 total shipments Bob hauled, 17 shipments, or 22%, had more than 500 feet of carry. In order to break even, he would have had to haul 204 shipments with no long carries or stair carries in addition to the 17 labor-intensive shipments.

Bob says that times are so tough that every driver he talks to claims s/he is looking for other work. Breakeven does not pay the bills! The only good side is that drivers who somehow manage to survive these lean times may have better opportunities at the other end of any shakeout.

Bob says he will lose greatly with the 400N tariff. He proposes that an exemption get applied for excessively long carries and stair carries, like going back to the way of charges were applied for apartments, condominiums, high rises, and mini-storage warehouses (the 400M tariff). Tariff 400N simply has no provision for jobs that are extremely labor-intensive. Bob believes that the Household Goods Tariff Bureau did not consult with drivers with experience and knowledge in coming up with this tariff.

With transportation essentially just covering cost, drivers are now forced to rely on pack jobs to make any profit (these jobs are not a normal function for road equipment). Up until last year, the carriers had military moves to prop up all the cheap COD and account work. Now, the military jobs are all very cheap, putting this industry is at a turning point. Movers must either charge more or find other work…

(For additional reading on these and related subjects see the forum postings under the header “Where Does Capacity Come From?” at the RELO roundtable.)

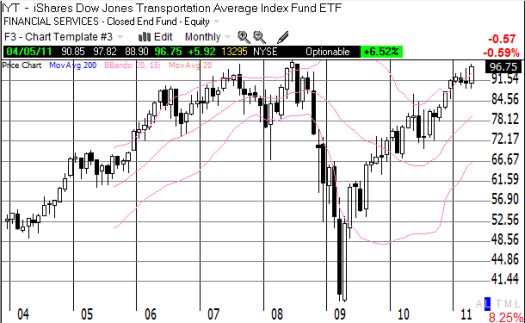

*Chart created using TeleChart:

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: no positions

I have been involved in this industry for 15 years. Tere is still alot to be said about it, outside Bob’s information. we have been getting hit in or wallets since I started in this industry. It used to be a profitable industry with profits hitting 250-350 a year, that is why I got invovled. With things the way they are now we are driving 1500 miles from home and staying out 5 weeks on end to carry home a 52k a yearprofit. What happened? We are more professioal than ever before, work harder for way less and invest ourselves to the point of risk is completely outside what is fair anywhere. Super Dave Mc.

Thanks for the additional background. I have been learning more and more about the industry and hope to keep writing about it in the future.

Here’s another blog addressing this subject:

http://fedupmover.blogspot.com/

Thanks for the additional reference!

Another spot more info is available:

http://www.worldwideerc.org/Resources/MOBILITYarticles/Pages/0508davis.aspx